History of the Basel Autumn Fair

Nowadays, the Basel Autumn Fair is the largest fun fair in Switzerland – with an unrivalled variety of fairground rides and original stalls. The tradition of this fair is deeply rooted in Basel; it is very much part of the old city. This is not surprising, especially when you consider that "d Hèèrbschtmäss" can look back on a long, exciting history that starts in the 15th century, with an emperor, a pope and a committed mayor. The Basel Autumn Fair has often changed in appearance over the centuries, adapting to the needs and circumstances of the times: Thus, it has survived the test of time and, in its unique way, has succeeded in remaining eternally young and fresh. A remarkable career for an event that was first rung in on 27 October 1471. Its unique history has shaped the "Hèèrbschtmäss" custom into something unique, which has delighted so many guests from Switzerland and abroad – from the very first day.

The “free city” of Basel was highly regarded in the 15th century. It was part of the “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation”, and lauded by its contemporaries for its prosperity, safety and extraordinary piety. These qualities were, in essence, the marketing tools of the time. They were the reason why the city on the Rhine knee was deemed worthy to host a great reform council of the Church.

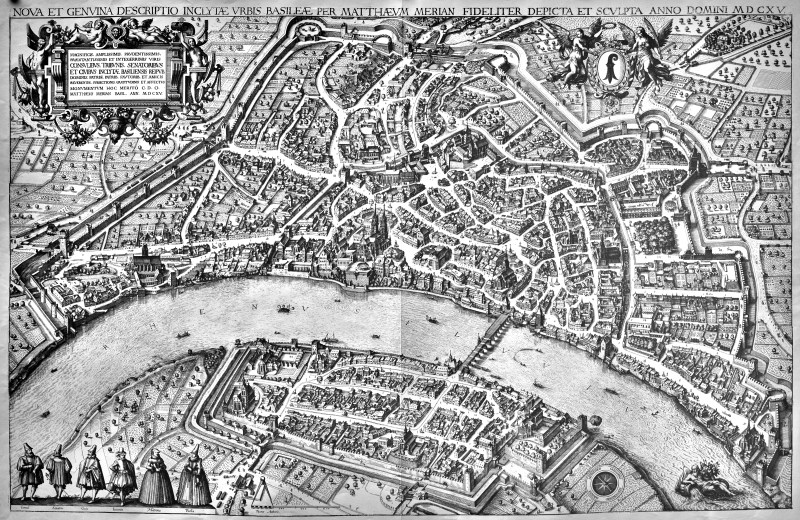

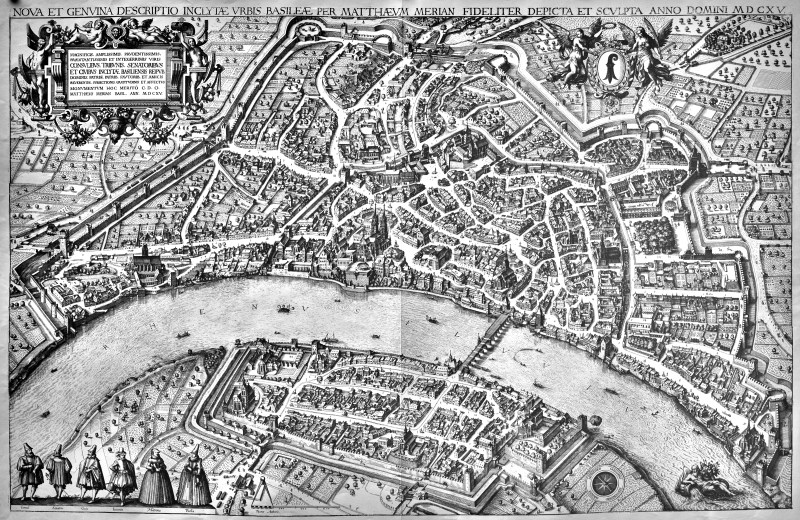

Merian Plan. More than 400 years ago, Matthäus Merian presented his bird's-eye view of the city of Basel to the Basel Council. Basel University Library

Such a gathering of the most important representatives of Western Christianity brought the host city considerable economic benefits: It brought more customers to trade and fill the inns, triggered urban development measures and brought the administration of the time additional revenue, which flowed into the public coffers in the form of road and bridge tolls, for example. The great Council of Basel met for almost two decades, from 1431 to 1449: two decades that permanently changed Basel's face; the Council triggered the momentous founding of the university, for example

Crisis follows council

However, in 1449, just in time for the end of the Council, the city fell into an actual depression. Diseases, famines and wars in nearby countries followed the golden years of prosperity. The locals started searching feverishly for ways to improve the economic well-being of the city. The establishment of a regular fair was meant to help with this, among other things– a weighty matter at the time even for a “free city”. Permission was required from the Emperor, then Frederick III, (1415–1493) from the House of Habsburg. However, this was not easy to obtain. Now they had to attract the monarch's attention. So, a delegation from the Rhine knee was sent to Rome to see Pope Pius II. (1405–1464) Delegation. This pope was well disposed towards Basel: His real name was Enea Silvio de' Piccolomini, and during the Council he had spent some time on the Rhine knee: People knew the Pope in the city. An advantageous situation. Pius II sent the Emperor a letter in 1459 recommending that he allow Basel to hold a fair.

Von Bärenfels makes it possible

Then the years passed – actually, a decade. Somehow the letter got lost in the machinations of the court bureaucracy of the time. It was the mayor of Basel, Hans von Bärenfels, who took up the fair project again ten years later. He began to persuade people, both at home and abroad, of the benefits of holding it. In the spring of 1471, the city council decided to "make a case to the keyser [Kaiser] for a fair". No sooner said than done: On Thursday, 11 July 1471, the mayor was finally handed a document with the emperor's seal. This important letter guaranteed the city of Basel the trade fair privilege "for all time".

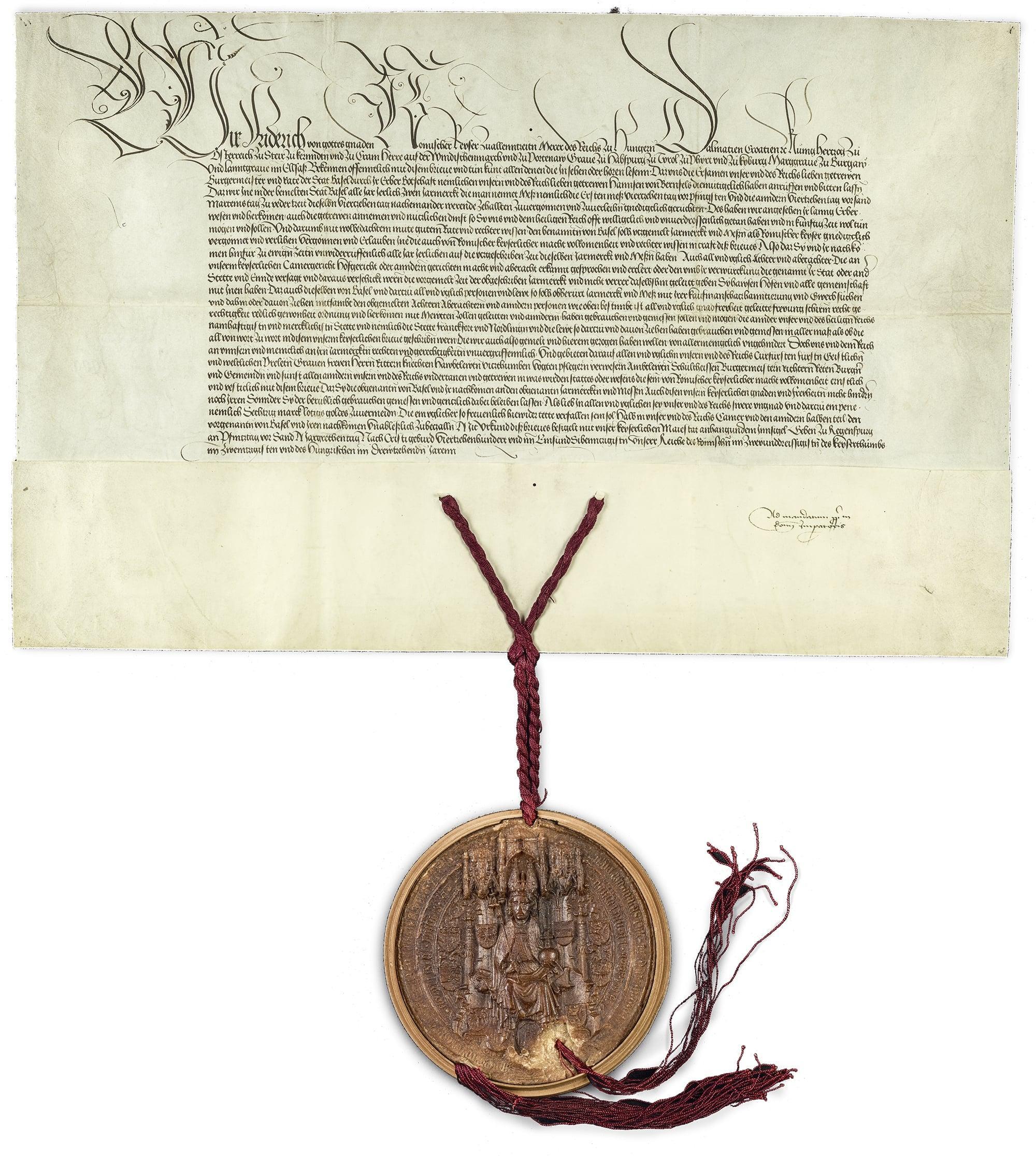

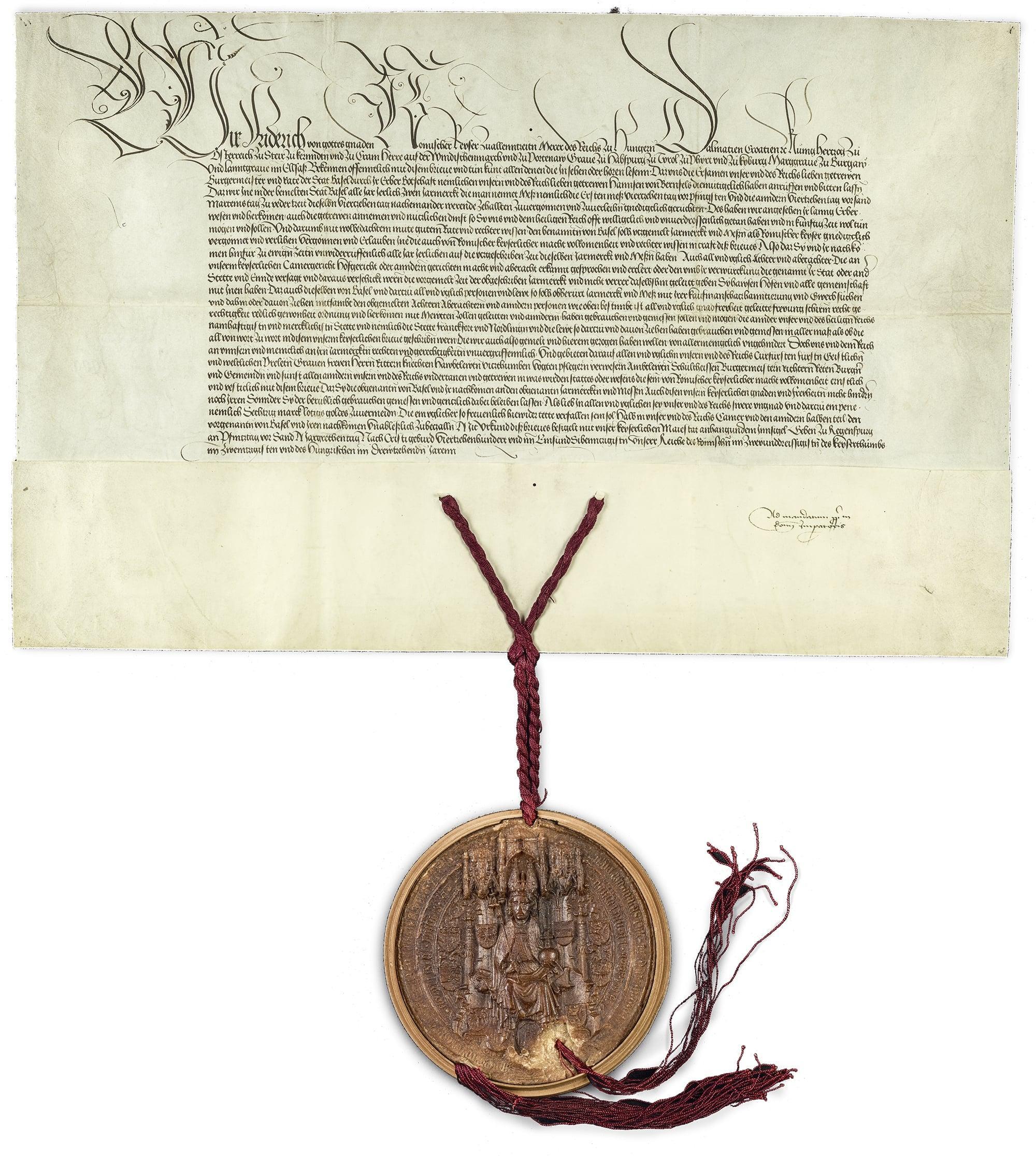

Privilege of Emperor Frederick III to open and hold two annual fairs, 11 July 1471. Source: “500 Years of the Basel Fair”, Helbing and Lichtenhanhn, 1971.

The emperor actually allowed Basel to hold two fortnightly fairs per year, one in spring and the other in autumn. However, the spring or Pentecost fair only took place for a short time and then disappeared into the mists of history. On 27 October 1471, Sabine's Day, the bells of the Basel town hall rang in the first Basel “Hèèrbschtmäss”, and the town clerk officially opened the Kornmarkt “in the name of God”.

Merchants, jugglers, prostitutes and crooks

Now, it was time for some relaxed, happy, enjoyable fairground fun within the city walls. Merchants offered their products for sale, food and drink were sold in great quantities, jugglers and singers showed off their skills, and all kinds of games and entertainment were offered to the people. But the event also attracted figures from the “underground” of the time to the city. Crooks, cardsharps, prostitutes and their pimps came to Basel to relieve the visitors to the fair, who flocked to the Rhine knee from all parts of Europe, of their savings.

Therefore, safety measures were taken from the very beginning. Three councillors were specifically responsible for the fair police. A specially convened five-member fair court adjudicated on cases of theft, violence and fraud – it also settled disputes between traders. Mounted mercenaries guarded all the roads into Basel; only selected city gates were open as this allowed better control of the flow of visitors. During the time of the Autumn Fair, foreign traders enjoyed the same rights in the city as local traders. Mysterious products from foreign lands were subsequently one of the big attractions of the first Autumn Fairs – and somehow this has remained the case to this day.

Rides, stalls, stands

So, it all started with delicacies and original goods from foreign countries. With bards, wrestlers, sporting competitions, jugglers, pickpockets, lottery games and every now and then a high wooden pole, sometimes greased, which brave men tried to climb to the cheers of the mob – hoping to find ham sausages, leather sacks filled with wine and similar fine prizes at its top. Today, the Basel Autumn Fair offers the latest ingenious mobile rides, from the free-fall tower to the roller coaster, through to wild rides whose passengers, almost resembling astronauts, soon no longer know where up ends and down starts. However, stalls presenting original goods and selling special nibbles are still an important part of the Fair. As far as sweets are concerned, the "Mässmogge", a sticky-sweet, deliciously shiny lump that comes in all colours, is the Basel Fair's number one speciality.

If you want to try a particularly historic sweet, you'll find it in Petersplatz. “Maagemòrsèlle” is a fairground speciality that was enjoyed by our ancestors. In contrast, the now popular candy floss is a rather young treat that has only been around since the 19th century; after all, its production requires a simple centrifuge, which is an industrial tool.

The carousel of fairground attractions

The sweets evolved in step with technological progress, as did the other attractions that a fair had to offer to captivate its customers. From the simple climbing pole to the looping roller coaster, it is a long road lined with attractions that are now history and others that have steadily evolved. Even in the earliest times, displays from the dubious zone of the unusual, even supernatural, played a major role at fairs. Mysteries, monsters and deformities were shipped from fair to fair centuries ago, paraded in stalls that were advertised outside by a barker: "See the wonders of this world, the bearded lady, the woman without a head or an abdomen, the Wolfman, Madame Venus – a medium who can read your most secret thoughts!" These attractions, called "sideshows" in the USA, were an intrinsic part of the Basel Autumn Fair for a long time. Elements of this survived into the late 1970s.

Stalls which featured magic tricks, feats of strength, animal training, musical performances and artistic skills were also very popular for a long time. There were real stars among these artists, such as the escape artist and strongman, Pius Buser from Sissach. In the period around the Second World War, his performances, which were partly based on the style of the great stage magician, Houdini, were the talk of the town during fair time. In the late 1950s, stalls suddenly appeared at the "Hèèrbschtmäss" where the then red-hot – and rather suspect in the eyes of many people – music styles of blues and rock 'n' roll were played. The 20th century also saw the dawn of the era of ever more technically sophisticated carousels and flying constructions: Technological progress and the use of electricity triggered the slow but steady triumphal march of the rides. The great era of the attraction stalls was over.

From the rolling barrel to the free-fall tower

The first attractions were mazes, simple ghost trains and things like the rolling barrel. The latter was a primitive version of the game with centrifugal force: The passengers simply leaned against the inner wall of a huge barrel, without a seat or seat belts. The thing then started spinning at a hell of a pace – and people found themselves stuck to the walls. Afterwards, masses of lost wallets and pocket watches had to be collected. Soon, mobile Ferris wheels also rose up in Basel, although their height was still – comparatively – modest at the beginning. As recently as the mid-1970s, the Basel Autumn Fair was the proud host of a Ferris wheel that was around 20 metres high; today, around 60 metres is the norm. This development exemplifies how fairground rides have changed: Higher and higher, faster and faster, wilder and wilder was the motto – and it has remained so to this day.

In the course of the 20th century, more and more new rides were created, some of them achieving the status of cult models: In the 1960s and 1970s, for example, these were the Himalayan rides and the ski lifts, fast spinning movements – at ground level or in the air – were the latest thing. Cult models that were all the rage at the time, such as Calypso, Voom Voom or Hully Gully, are still seen today in some of the fairgrounds scattered around Basel's inner city. Next to them are their grandchildren: technically complex, head-down driving pleasures that elicit screams of fear and delight from their passengers. The Basel Autumn Fair has always been on the cutting edge with its repertoire – and it has remained that way. It offers a selection of attractions for a wide range of tastes and age groups that is second to none in the country.

Messeglöckner, a Basel honorary office

Thus, the face of the custom has changed in the mighty current of time over the centuries. And it has always remained a crowd puller for guests from home and abroad. In times of crisis, for example at the end of the 1920s, "d' Hèèrbschtmäss" was at times subdued, only to then flourish again. The urban squares where the attractions are located underwent a change. But in Basel, fortunately, pleasure always remained interwoven with inner-city life and was present at several venues. A circumstance that greatly contributes to the uniqueness of the fair: It was never displaced to a peripheral location far outside the inner city, as has happened in many other cities. That is why the connection of the people of Basel to their "Mäss" and its traditions is so strong: that deep connection, especially to special aspects of the fair, such as the "Hääfelìmäärt" on Petersplatz, which has been a real treasure trove of ceramic goods since the 19th century.

Another beloved Basel tradition is the annual ringing in of the Autumn Fair from the tower of St. Martin's Church, which attracts many spectators to the Martinskirchplatz. The ceremonial act always takes place on the first day of the Autumn Fair, which is the Saturday before 30 October. In the past, the church's sexton provided this office. For decades now, it has been provided by dedicated private individuals – with the greatest care and respect for tradition. For a long time now, Franz Baur, a man who knows his home town of Basel like the back of his hand and is deeply connected to its traditions, has been in charge of ringing the legendary bell in the traditional manner. As a reward, he receives a pair of gloves every year, just like his predecessors. Staggered, however: he gets one glove after the ringing in, the other after the ringing out of the "Hèèrbschtmäss". Only when all the autumnal glory has run its course can he enjoy the fruits of his labour and put on both – a sign of Protestant-tinged caution on the part of the principals. Typical Basel.

About the traditions

and Add to home screen

and Add to home screen